Linux Forensics

Written on May 12th, 2020 by Caitlin Allen

For the entire semester at my internship, I got to dive into learning about Linux forensics while also taking a 6 week long course on Linux forensics at Champlain. I was introduced to command-line tools, TSURUGI Linux, and now seem to know the Linux filesystem like the back of my hand. We don’t get to learn much about Linux forensics at Champlain, I’m only a digital forensics minor, but I’ve only learned how to examine Windows machines. But Linux makes up 90% of cloud infrastructure, about 96% of the top 1 million web servers, and all supercomputers, at least according to this source. If a web server gets infected with ransomware or a server that deals with PII or sensitive data needs to be investigated for exfiltration, you’ll need to know how to investigate it. Knowing what tools to use, where logs are stored, and what logs what are some basics we’ll cover to get you up to speed on how to perform a forensics analysis on a Linux host.

History of Linux

Before we dive into how to perform an analysis, lets talk about the history of Linux briefly. Linux’s roots are in not only Unix, but also Multics. Both of these had a shared goal of developing a robust multi-user operating system. Most people are aware of the roots in Unix, but Multics, the Multiplexed Information and Computing Service, was a time-sharing, or sharing of computing resources with many users at the same time (for simplicity, multitasking), operating system. This operating system was initially planned and began to be developed starting in 1964 that was led by MIT in cooperation with General Electric and Bell Labs. The developers at Bell Labs who were working on Multics were interested in building a multi-user operating system that had single-level storage, dynamic linking, and a hierarchial file system. Ken Thompson was one of the Bell Labs developers who liked the potential of Multics, but felt it was too complex and wanted to explore simpler solutions for what their goals were. In 1969, Bell Labs pulled out of the project.

Thompson went on to write the first version of Unix in 1969, it was actually called UNICS (Uniplexed Operating and Computing System), but was shortened to Unix. Dennis Ritchie, who wrote the first C complier, teamed up with Thompson and they rewrote the Unix kernel in C. The kernel now being written in C in 1973 had made this operating system portable, unlike any operating system of its time! From the time of the kernel being rewritten to Linux being developed, other Unix-based systems would be developed. The University of California Berkeley’s Computer Systems Rsearch Group would go on to write FreeBSD, Sun Microsystems was selling low-cost high-performance desktops running Unix, and Richard Stallman would start the GNU Project with the goal of creating a free Unix-like OS. In 1987, MINIX, a Unix-like system for academic use was released, but this pricy academic OS was the reason Linus Torvalds would go on to develop Linux.

In 1991, Linus Torvalds, a computer science student at the University of Helsinki, bought a computer that came with MS-DOS. He wanted to use a Unix operating system and went out to try and buy MINIX. The pricetag of $5000 was not affordable, and thats when Torvalds set out to develop Linux.

Using MINIX and the GNU C Complier, Linus developed what he wanted to call “Freax”, but an admin of the FTP server he uploaded his files from development to thought that was not a good name and actually named the project Linux on the server without asking Torvalds, who eventually thought it was a good idea. He did not want to be too egotistical and prior to calling it Freax actually considered Linux.

The Extended File System

If you’ve used Linux before, you’ve probably been using the extended (EXT) filesystem. The extended filesystem is one of many filesystems used by the Linux kernel. It was implemented in April 1992 specifically for the Linux kernel, overcoming the limitations of the MINIX filesystem. ext was the first to be implemented, followed by ext2 and Xiafs. Xiafs you have maye heard of, its based on the MINIX filesystem and now obsolete, but originally more stable than ext2. However, since it was basically a minimalistic modification of the MINIX filesystem and ext2 was evolving to improve the stability of it, Xiafs would not go on to be used in Linux for long. ext3 and the now current ext4 then followed in use. ext4 was released in 2008 with improved performance, reliability, and capacity.

The Other Filesystems

Linux supports so many other filesystems, most distributions just default to ext4 but if you’ve used CentOS 7 or RHEL 7, the default filesystem is actually not ext4 and instead XFS. Just to name a few, theres BtrFS (Pronounced either “butter” or “better”), ReiserFS, ZFS, XFS, and JFS. Each filesystem has different goals and abilities.

BtrFS

Based on the copy-on-write principle, BtrFS was designed by Oracle to be used in Linux. BtrFS is an abbreviation for b-tree filesystem, B-tree meaning a self-balancing tree structure that maintains the data and allows for searches, sequential access, insertions, and deletions. B-tree is useful for storage that will need to read and write large blocks of data!BtrFS focused on scaleable storage, not just by size, but also with administration and management to make it more reliable. SUSE Linux Enterprise Server 12 in 2015 adopted BtrFS as the default filesystem!

ReiserFS

ReiserFS has some pretty interesting lore around it, the leader of the development team, Hans Reiser, was convicted of murder in April 2008 which delayed the development of this filesystem. When I researched ReiserFS that was one of the most interesting facts I saw.

This journaled filesystem was developed by a team at Namesys and is still supported by the Linux kernel. ReiserFS offered a few features that no other existing filesystem for Linux had at the time like metadata-only journaling, online resizing that allowed for growth (shrinking could be done offline!), and tail packing which reduced fragmentation.

ZFS

Designed by Sun Microsystems, the Z Filesystem is scalable and has extensive data corruption protection and integrates many concepts that allow for precise configuration. ZFS is unusual from other storage systems since it acts as both the volume manager and filesystem, so it has complete knowledge of the physical disks and volumes. It ensures that data stored cannot be lost due to physical errors or misprocessing. ZFS is a great solution for long-term data storage and storing data that you want zero data loss with!

XFS

As mentioned before, XFS is now the default in CentOS 7 and RHEL 7. This filesystem supports metadata journaling for quicker crash recovery times, supports very file large sizes, and has better I/O scabaility using b-trees so that user data and metadata can be searched.

JFS

The Journaling Filesystem does exactly that, journal. This filesystem keeps track of changes not yet commit to the filesystem by recording the changes being currently made in the “journal”. Like XFS, it has quicker crash recovery times and this is thanks to the journal since data corruption is less likely to happen when you can use the journal. This filesystem was created by IBM so there are also JFS versions for their operating system, AIX. What makes JFS journaling unique is that journaling was not an add-on to the filesystem, but it was implemented from the start with the intent to journal. JFS only journals metadata and is actually similar to XFS since they only journal parts of the inode (data structure that described a file-system object like a file).

Why should we care about Linux forensics?

Now that you know a bit more about Linux, you need to know why you should care about Linux forensics. You might be surprised to learn that a lot of the commonly used GUI based forensics tools can’t read most Linux filesystems. If you like using tools like EnCase or Axiom but find yourself needing to investigate a Linux host using a filesystem not supported by either tool, you’ll now need to try and figure out how to investigate it. Knowing what tools you can use and what different ways you can investigate makes this process so much faster, so instead of having to do this when you have a case to investigate, you can prepare now and be familiar with your new forensic toolkit additions.

We’ll talk about command-line tools and your typical GUI tools!

GUI-based toolkits

Magnet Axiom

I’ve been to the Magnet User Summit and got to learn a lot about Axiom so I may be biased, but I love Axiom. However, Axiom only supports ext2, ext3, ext4, and F2Fs (Flash-Friendly Filesystem). Many toolkits seem to support ext now, so if you prefer EnCase over Axiom and need to investigate anything ext related, you have flexibility in what tool you get to use.

EnCase

EnCase is a tool all of us at Champlain are familiar with, a professor of ours helped with developing it! EnCase is able to read the ext filesystem, and can also parse AIX and Solaris images which is pretty neat. Theres also a Linux acquisition tool for live forensics called LinEn.

FTK Imager

AccessData’s FTK Imager was the first toolkit I ever touched, and despite being free, is still an awesome tool to use. FTK Imager supports the ext filesystem. If you don’t have the money lying around for a license but want to try your hand at investigating a Linux host, FTK Imager is a reliable tool!

X-Ways

Unfortunately I have still yet to get access to a license of X-Ways to try it out, but from DFIR colleagues I’ve only heard great things about X-Ways! This supports the most filesystems out of any forensics tool. They support XFS, variants of UFS, HFS, and ReiserFS. While it does not support every filesystem in the world, it supports a lot more than the above tools.

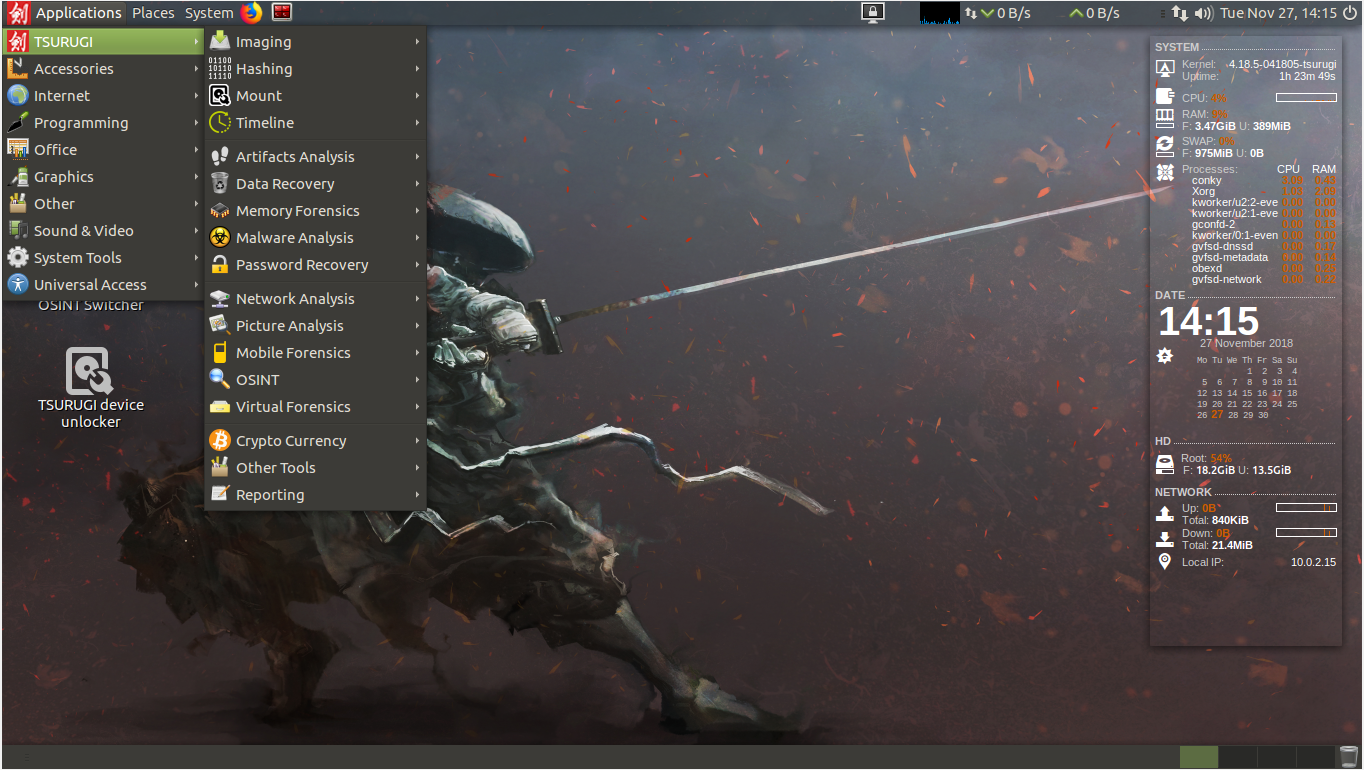

Command-Line Tools

The command line is probably not a favorite with many to use, theres no tree structure to help you click on where you want to go, theres no window showing you whats inside the file you clicked on, and you need to be familiar with the filesystem. However, command-line tools don’t need to power a GUI and run at minimal configurations, making them extremely fast and efficient. Large images can be quickly processed and parsed, which means you don’t need to run something overnight or awkwardly sit at your desk and realize you have nothing to do but sit and wait. A Linux distribution called TSURUGI Linux comes pre-loaded with a ton of command-line tools you’d need. Its built for forensics and makes investigating with the command-line a lot easier. You don’t need to use TSURUGI Linux to investigate, you can use any Linux distribution you’re familiar with, but TSURUGI gets rid of wasting time downloading tools.

EWF Toolkit

The Expert Witness File/Format toolkit is full of useful tools:

- ewfacquire: An acqusition tool I’ve used before and found simple to use.

- ewfacquirestream

- ewfdebug: Non-functional tool at the moment

- ewfexport: Exports to RAW format or specific version of EWF files

- ewfinfo: Shows metadata

- ewfmount: Mounts your image for investigating

- ewfrecover: Creates a new set of EWF files from a corrupted set

- ewfverify: Probably the most important tool, this verifies your images to make sure nothing was changed or corrupted during acquisition After acquisition with ewf, I recommend making a case directory and working out of there. Just makes everything a lot easier for organization.

The Sleuth Kit

If you’ve used Autopsy, you’ve used the Sleuth Kit. This tool helps power the popular GUI tool. The Sleuth Kit has lets you create timelines, can output the contents and details of image files, lookup hash values in a hash database, and so much more. This website has all the different commands and what they do, along with the general syntax. A great tool to know some commands for!

Volatility

The Volatility Framework is a memory forensics tool that supports analysis for not just Linux, but also Windows, Mac, and Android memory. It can analyze raw dumps, crash dumps, VirtualBox dumps, VMware dumps, and much more. You can view running processes on a system, use the KPCR Plugin (Keneral Processor Control Region) which scans for those structures and analyzes processor-specific data. Volatility is an interesting tool that I’m trying to become more familiar with since its super cool and has a lot of capabilities!

The Takeaway

Get to know Linux forensics! Theres so many different tools and this post barely scratches the surface on Linux forensics. This is just the tiniest bit of information I’ve learned this past semester on Linux forensics and I didn’t want to write a novel or overwhelm anybody. But TL;DR, you should care about Linux forensics.